Bad Boy Pistons center Rick Mahorn had already warned Atlanta Hawks superstar Dominique Wilkins about pump fakes.

No pump fakes when Wilkins comes into the lane. Wilkins did not listen. He thought he had Mahorn set up to score easily in the lane. He pump faked. Mahorn went soaring into the air. He then came down hard on Wilkins, sending him crashing to the floor.

“That is what you’re going to get every time you pump fake,” Mahorn barked at Wilkins.

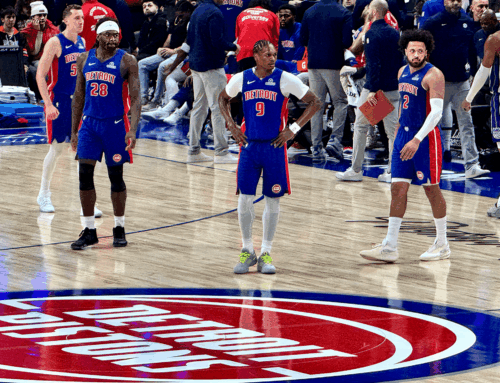

Mahorn played defense with an edge. The Pistons cannot employ many of Mahorn’s tricks of the trade. However, they could use his attitude on defense. The current Pistons (3-12) do not lose games because they lack talent. They lose games because they are small and do not put forth the same effort on defense as they do on offense.

Only San Antonio (119.7 points per game) gives up more points than the Pistons (118.2). Opponents shoot 47.9 percent against the Pistons and out rebound them 47.1 to 44.2. Mahorn believes it is unfair to come down too hard on the Pistons lack of defense because nobody plays defense anymore.

“It’s the first team to 150 points who wins,” he joked.

The Pistons two championship teams had one thing in common. They had rim protectors. Ben Wallace was the best rim protector in Pistons history during the 2004 champion Going to Work team. He swooped from nowhere to block shots when a guard lost his man. No one feared the Fro because of Big Ben’s offense. They feared the Fro because he was strong and physical and his primary role was to prevent guys from scoring. He is in the Naismith Hall of Fame because he was a four-time defensive player of the year.

During the Bad Boys era, 7-foot-1 reserved center John Salley served as the rim protector. Bill Laimbeer and Mahorn were lane protectors. Opponents thought twice about driving the lane against the Pistons because they never knew if a Mahorn or Laimbeer hip, elbow or chest bump awaited them.

(AP Photo/Bob Galbraith)

Mahorn said he and Wallace became more defensive orientated because they both were after thoughts in the draft and needed a way to stay in the league. Few were willing to sell out defensively in the NBA. Mahorn and Wallace were.

Mahorn attended Hampton Institute, which opponents jokingly called Hamster Institute to bother him. He was drafted in the second round. Wallace went undrafted after attending Cuyahoga Community College and Virginia Union.

“We were hungry,” Mahorn told Woodward Sports. “And we had to represent coming from small black colleges.”

Wilkins drove the lane with hesitation against the Pistons.

“Nique knew when to come into the paint. He didn’t when the big dogs were in there barking,” Mahorn said. “If you were going to beat me I was going to make sure you paid for it.”

Mahorn learned from Wes Unseld, an undersized 6-foot-8 center with limited athletic ability who played for the Washington Bullets. Unseld unleashed a bulldog mentality whenever he played.

“That’s how I played the game,” Mahorn said. “It’s about positioning in the game. You must wedge a guy out.”

While the old school Pistons chose to ground and pound, the current Pistons are often spectators.

Let’s cut back to a recent game against the Boston Celtics. Celtics guard Jason Tatum received a pass as he drove toward the lane. Three Pistons were inside the paint marveling at his speed and grace. Tatum finished with a nice reverse layup and the three Pistons did nothing to stop him. Unacceptable.

Mahorn would have stood over Tatum after knocking him to the ground. Wallace would have swatted the ball into the 20th row.

The current Pistons may as well have broken out the buttered popcorn to enjoy the show.

Mahorn and Wallace had something else in common. They gave spirited lectures if they believed teammates were slacking on defense. Wallace laid down the hammer several times when he believed he was losing the alpha dog role to guard Chauncey Billups. He brought fear to teammates. Often the Pistons locked down defensively after being scolded by Wallace.

The current Pistons could use a guy like that.

Follow me on Twitter @terryfosterdet